When the nice and cozy summer weather begins, you might end up worrying concerning the beloved pets and other animals we live in close proximity to. But fur and hair are ancient adaptations that allowed human ancestors to have a more lively lifestyle and a varied weight-reduction plan.

All mammals have some type of fur. This is an element of what separates us from other groups of animals. Fur is available in all shapes and kinds, including human hair. Its thermoregulation properties can tell us how our ancestors' lifestyles modified as they transitioned from reptiles to more lively hunters.

Mammals are highly social and fur color also helps distinguish allies from enemies. It also can help animals hide. Think of a sand-colored fox within the desert or a polar bear within the snow.

Birds are known to have evolved from reptilian dinosaurs and feathers have highly modified dinosaur scales. The origin of mammalian hair in deep time is less clear because hard scales, bones, and feathers are higher preserved than other forms of tissue.

Fossil impressions of hair are present in Middle Jurassic species, Like a beaver About 220 million years ago. and a mammalian ancestor with fossilized fur, like a mouse which had a mohawk of bristles, is understood from the Cretaceous period, 125 million years ago.

Such fossils are rare.

But scientists have found food stays containing hair-like structures inside fossilized feces from the Permian period, about 260 million years ago.

However, we are able to take a have a look at the evolution of mammalian ancestors to realize a greater understanding of the evolution of fur and hair.

We know that the mammalian and reptilian lineages diverged about 300 million years ago. Early mammalian ancestors still looked very very like reptiles.

But that they had one. Different food. They hunted larger prey with their teeth, while reptiles primarily ate up small spiders, millipedes, or insects.

A relentless temperature is important for mammals, which you would like for hunting. This could be completed by, amongst other things, developing fur.

Prey also requires spontaneous movement akin to running and pouncing on prey. Daily sunbathing, against this, is important for agility in reptiles, which sit on warm rocks and wait for insects to pass by.

The first animals to experiment with body temperature were the mammalian predecessors, the early synapsids. Some of them had large lizard-like bodies and evolved. Ships on their backsSupported by the outgrowths of the vertebrae.

Thanks to a dense blood vessel system on the surface of the skin, these sails could quickly absorb the sun's heat and expel excess body heat (very like today's elephants and fennec foxes with their large ears). do from). But this strategy didn't work for them: the ancestors of sailing mammals became extinct.

The ancestors of early mammals still had typical reptilian scales, with their poor thermoregulation properties. This is shown by Fossilized abdominal skin 275-million-year-old (mid-Permian) animal footprints present in Poland in 2012.

Wolfgang Gerber/University of Tübingen, CC BY-NC

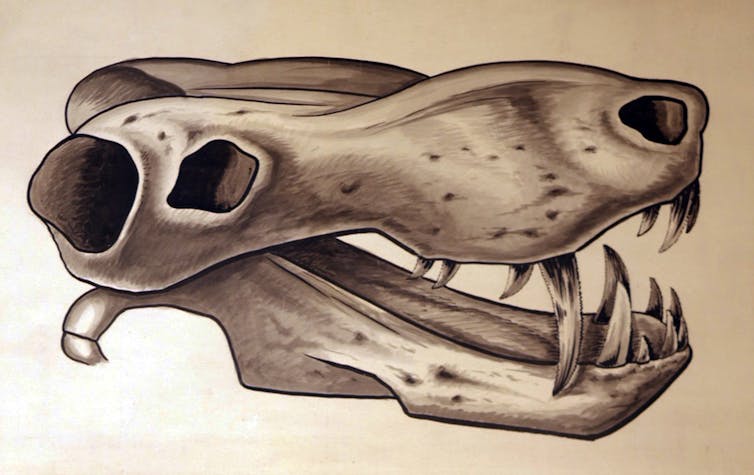

In the Upper Permian period, 255 million years ago, the earliest mammalian ancestors lived. One of essentially the most complete and exquisite specimens of this fossil animal exists within the paleontological collection of the University of Tübingen, Germany.

This specimen was present in the Useli Formation, Rohoho, Tanzania and was considered one of the biggest predators of its time. It still looked like a reptile, but already had an upright body posture, more energetic than running. Stretched limbs As reptiles do.

Theodore Bowman (1855-1932), CC BY-NC

to make use of Model of Tübingenbiologists showed in 2021 that early synapsids already had higher metabolic rates than reptiles. Indications for this are the big alimentary canal, a small tunnel along the alimentary artery within the bone of the upper limb (femur). Mammalian nutrients are larger than that of reptiles.

Moreover, unlike reptiles, and other Permian species, there may be an in depth blood supply. Highly vascularised snout. Small holes within the snout bones of those animals may indicate the opening of blood vessels to support nerve pathways and whiskers (vibrissae).

Whiskers are snout hairs specialized for tactile functions, popular in modern mammals akin to cats. They could have been the primary to develop hair and only later did fur develop.

Dinosaurs evolved at the top of the Triassic period, about 233 million years ago, several million years after the primary evidence of hair in mammalian precursors. But the earliest dinosaurs were already so simple as hair. Feather precursorswhich later diverged into multiple barbs, shafts and barbules, and later into vanes in additional bird-like dinosaurs.

Are mammalian hair product of scales, like feathers? Yes and no.

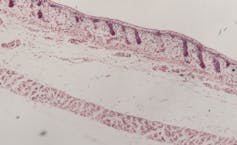

In early embryonic development, all land vertebrates have a thick layer of skin called the placode. This Genetically induced cell condensation are Precursors of all skin appendages — Scales, feathers and hair alike. Hair and feathers depend on the identical genetic program.

University of Tübingen, CC BY-NC

But later in embryonic development, the structures tackle completely different forms. The topmost layer of skin folds to form scales and feathers. However, the skin is manipulated to permit hair to grow beneath the surface of the skin. The hair shaft emerges from the follicle pocket only laterally.

University of Tübingen., CC BY-ND

In evolution, hairs, scales, and feathers originally served an identical function: thermoregulation and display. Birds developed an entire flight apparatus long after the primary feathers emerged.

Many mammals later lost their thick fur, akin to whales (which developed fat storage as an alternative choice to regulate body temperature) and humans. It isn't clear why humans lost most of their fur Some scientists think so This was to maintain cool during long hunts on the new savannah.